An empirical exploration of why arithmetic models sometimes neither memorize nor generalize

(Part 2 of an ongoing exploration into how small language models learn arithmetic)

In the previous post, I described an experiment that started with a simple goal:

to observe memorization and eventual grokking in a small language model trained on arithmetic operations.

The setup was straightforward.

The expectation was almost textbook.

Train long enough → memorization emerges → test loss collapses → generalization appears.

But what actually happened was far more interesting.

This post documents what I observed after extending training to 1,000 epochs, why the expected “grokking moment” never arrived, and what this reveals about the tension between memorization, optimization, and learning in language models.

Recap (Brief)

In Part 1, I trained a small transformer (DistilGPT-2) on synthetic arithmetic data involving addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

The goal was to observe:

- Whether the model would memorize the dataset

- Whether memorization would precede generalization

- Whether a clear grokking phase would emerge

By ~300-500 epochs, something curious was already happening:

- Training loss was decreasing slowly

- Evaluation loss was also decreasing

- Yet the model was still producing many incorrect numeric outputs

This contradicted the simple story that:

“Models memorize first, then generalize.”

So I kept training.

What happened after 1000 epochs

At ~1000 epochs, the picture became clearer — and stranger.

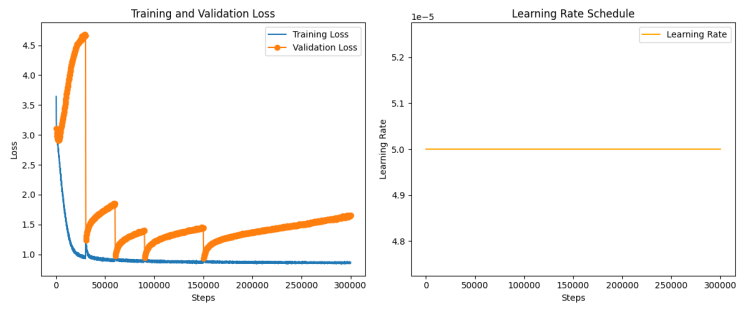

Observed metrics

- Training loss plateaued around 0.86

- Evaluation loss drifted upward toward 1.6

- Gradient norms remained stable

- No sudden phase transition

- No collapse into perfect memorization

Despite massive training time, the model never entered a regime where it simply “remembered” the dataset.

Yet it wasn’t random either.

What the model was actually doing

When inspecting predictions, a consistent pattern emerged:

- The operation was almost always correct

(addition, subtraction, division identified correctly) - The magnitude was often close

- The digits were frequently wrong

Example:

Input: SUBTRACT 521 601

Output: -808088512

Target: -80

or

Input: DIVIDE 845 79

Output: 10.69620253

Target: 10.69620253164557

This wasn’t noise.

This was structure without precision.

Why memorization never happened

At first glance, this seems odd.

The dataset was small (~10k examples).

The model was large enough to memorize it.

So why didn’t it?

The answer lies in how the optimization problem was shaped.

Memorization was expensive

To memorize arithmetic examples exactly, the model would need to store long token sequences with high precision.

That means:

- remembering long digit strings

- learning exact termination behavior

- assigning high confidence to precise token sequences

This is expensive in parameter space.

In contrast, learning approximate arithmetic rules is cheaper.

SGD naturally prefers solutions that:

- reduce loss quickly

- generalize across many samples

- reuse shared structure

So the model took the path of least resistance.

It learned how arithmetic behaves without committing to exact outputs.

The loss function rewarded “almost right”

Language modeling loss is token-based.

That means:

- If the model predicts most digits correctly but misses a few,

- It still receives useful gradient signal.

So during training, the model is constantly reinforced for being approximately right.

This creates a subtle but powerful effect:

The model is rewarded for learning the procedure, not the exact answer.

In other words, the optimization objective quietly prefers understanding over memorization.

Why grokking never appeared

Classic grokking shows a sudden collapse in test loss after long stagnation.

That phenomenon usually requires:

- Strong regularization

- A sharp transition between rule discovery and rule application

- A training signal that punishes partial correctness

In this experiment:

- The loss never became harsh enough

- Partial correctness was always rewarded

- There was no incentive to “snap” into exact symbolic computation

So the model stayed in a stable middle ground:

It learned how arithmetic works, but never felt pressure to be perfect at it.

Between Two Worlds

This experiment ended up living in an interesting middle space.

Not memorization.

Not grokking.

Something in between.

The model learned enough structure to behave intelligently,

but never crossed the threshold into exact symbolic computation.

It was neither guessing nor recalling.

It was reasoning — approximately.

That, in itself, is revealing.

What this tells us

- Memorization is not the default outcome of training — even with enough capacity.

- Grokking is not inevitable — it requires specific pressure.

- Optimization dynamics matter more than model size.

- Language models can behave like approximate algorithm learners without ever becoming exact ones.

Or put more simply:

The model knew what to do long before it knew how to do it perfectly.

What could be a cool experiment next

I haven’t decided what it will be, yet!

Possibilities include:

- Changing the loss to punish approximation

- Reducing vocabulary to force symbolic precision

- Isolating arithmetic types (addition only)

- Or pushing the same setup until it breaks in an interesting way

For now, I’m leaving the experiment here — not as a conclusion, but as a checkpoint.

Appendix (for readers who want details)

- Model: DistilGPT-2

- Training: ~1000 epochs

- Task: Mixed arithmetic (add / subtract / multiply / divide)

- Key observation: sustained partial correctness without memorization

- Artifacts:

If you’ve read this far, you’re exactly the audience this experiment was for.

This wasn’t about getting a model to work.

It was about watching how learning actually unfolds when nothing forces it to be perfect.

And sometimes, that’s where the most interesting behavior lives.