An experiment in memorization, grokking, and misleading loss curves

This post documents an experiment that didn’t go the way I expected.

What started as a simple attempt to observe memorization and grokking in arithmetic models turned into a deeper lesson about how misleading loss curves can be — especially for algorithmic tasks.

What I expected to see

I went into this experiment with a fairly standard mental model of how learning unfolds in neural networks, particularly for structured, rule-based problems.

The story usually goes like this:

- Training loss collapses first, as the model memorizes patterns in the training data.

- Evaluation loss remains high, because the model fails on unseen examples.

- After sufficient training, evaluation loss suddenly drops, signaling grokking — the moment the model discovers the underlying rule and generalizes.

Arithmetic felt like an ideal testbed for observing this behavior. The rules are precise. The outputs are unambiguous. There’s nowhere to hide behind semantics or subjective interpretation.

I expected the training loss curve to tell a clean, familiar story.

That’s not what happened.

The experiment (briefly)

I fine-tuned a small transformer (DistilGPT-2) on synthetic arithmetic tasks:

- Operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication, division

- Inputs: structured text (e.g.,

DIVIDE 845 79) - Outputs: exact numerical answers

- Training setup:

- Constant learning rate

- Weight decay

- Long-horizon training (500+ epochs)

- Standard cross-entropy loss

The goal wasn’t performance or benchmarking. It was to observe learning dynamics in a controlled setting.

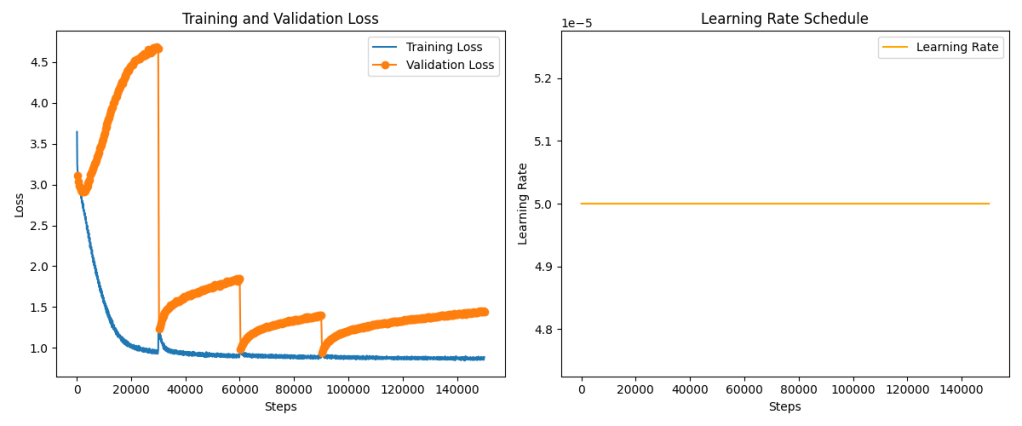

The first surprise: loss curves didn’t behave as expected

What I saw early on was confusing:

- Training loss decreased slowly and stubbornly.

- Evaluation loss dropped dramatically — early and consistently.

- Gradients were stable, learning rate constant, and training entirely well-behaved.

At first glance, this didn’t make sense.

If training loss represents memorization, and evaluation loss represents generalization, how could the model be generalizing before it memorized?

The loss curves suggested confusion.

But they weren’t unstable or noisy — they were calmly telling a story I didn’t yet understand.

When loss curves stopped explaining what was happening

Trying to reason purely from the curves got me nowhere.

So I stopped staring at the loss and started looking directly at the model’s outputs.

That’s where things finally clicked.

Looking at predictions changed everything

| Operation | Input | Expected Output | Model Output | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIVIDE | 845 ÷ 79 | 10.69620253 | 10.69620253 | Correct to several decimals |

| DIVIDE | 356 ÷ 936 | 0.38034188 | 0.3165618 | Numerically close, wrong digits |

| SUM | 568 + 390 | 958 | 958 | Exact match |

| MULTIPLY | 974 × 915 | 891210 | 8912101025 | Correct structure, failed termination |

| SUBTRACT | 190 − 498 | -308 | -308781889 | Correct sign, magnitude explosion |

Once I inspected individual predictions, clear patterns emerged.

The model was often:

- Applying the correct operation

- Producing values with the right order of magnitude

- Generating numerically close answers, especially for division

But the answers were still wrong.

And in arithmetic, close is indistinguishable from incorrect.

One extra digit.

One misplaced decimal.

One failure to stop generation at the right time.

From the perspective of cross-entropy loss, these are complete failures.

Behaviorally, they tell a very different story.

The model almost always applies the correct operation, even when the answer is wrong.

Arithmetic is unforgiving — and loss reflects that

Arithmetic exposes a fundamental weakness in token-level loss metrics:

- Partial correctness is invisible.

- Near-correct answers receive the same penalty as wildly incorrect ones.

- One wrong digit invalidates the entire sequence.

This is especially severe for division. Predicting 0.316 instead of 0.380 is numerically close, but token-wise it’s treated as fully wrong.

This leads to an important realization:

The model learned the rule long before it learned precision.

Loss does not acknowledge that.

A reframing that made things click

At some point, I wrote this down while reviewing outputs:

“I know how to compute, but I haven’t learned the termination constraint.”

That single sentence explained many of the failures I was seeing:

- Correct digit-level computation

- Correct sign and scale

- Failure to stop at the right point

- Extra digits appended to otherwise correct answers

This isn’t random guessing.

It’s incomplete algorithm execution.

Which leads to the core insight of this experiment:

The model didn’t fail to learn arithmetic — our metrics failed to notice when it did.

Loss vs learning

This experiment forced me to rethink what loss curves are actually measuring.

The distinction that matters is this:

Grokking is about representations.

Loss is about tokens.

For arithmetic tasks, these two can drift far apart.

That’s why evaluation loss can improve early, training loss can remain high, and the model can look “dumb” long after it has learned the underlying rule.

Put more bluntly:

Loss curves can lie badly for algorithmic tasks.

The wrong question — and the right one

Early on, I kept implicitly asking:

Is the answer exactly right?

But that turned out to be the wrong question.

The more informative question is:

Is the model executing the correct procedure?

Once I started evaluating predictions with that lens — including decimal-aware comparisons for division — the behavior made sense.

What this does (and does not) claim

This experiment does not prove that:

- The model “understands” arithmetic in a human sense

- Grokking has already occurred

- Loss functions are fundamentally broken

What it does suggest is more subtle:

Arithmetic models don’t fail because they haven’t learned the rule — they fail because our metrics demand perfection before acknowledging understanding.

That distinction matters, especially when studying learning dynamics.

What happens next

Training is still ongoing beyond 500 epochs.

If classical grokking appears, I expect to see:

- A sharp collapse in training loss

- A discrete jump in exact-match accuracy

- The disappearance of termination and precision errors

Or it may not happen at all.

Either outcome is informative.

For now, the most interesting result isn’t whether grokking eventually happens —

it’s how much learning can occur before our metrics notice it.

One thought on “Why arithmetic models look dumb long after they’ve learned the rule”